Common practice to play cricket…

Peckham Rye Park partially owes its existence to cricket. When locals wanted to play the game in Victorian England, they converged on Peckham. Some of the matches descended into vicious acts of revenge and other passing pedestrians were in fear of being struck by the sloggers at the crease.

HUGO SIMMS recalls the resulting search for a safer spot and how, decades later, it has now returned to its original home, under the watchful eye of two of Surrey’s current cricket stars.

Anyone strolling through Peckham Rye Park along the Colyton Road end this autumn would have noted the appearance of a large metal-framed structure, wrapped in netting.

Was someone growing small fruit? Perhaps some kind of airy self-isolation chamber?

A grand opening at the end of September revealed the truth.

They are in fact cricket nets, two of them, used for the practice of the sport.

Young cricketers in whites from Streatham and Marlborough Juniors lined up to hurl balls down to batting colleagues at the other end.

Behind the wickets, side-footing the balls back to each bowler, stood two professional cricketers – Surrey and England’s Ollie Pope and Bryony Smith.

After two hours of vigorous training, and with the light fading, the children had cricket equipment signed and questions answered by the duo.

This event not only announced the arrival of the new nets, it also signalled the renewal of a lengthy association between cricket and Peckham Rye.

As long ago as the 1820s, William King, landlord of the Kings Arms Tavern, resplendent on the corner of Peckham Rye and East Dulwich Road with commanding views of the Kentish and Surrey Hills, offered guests the use of bats, balls and wickets for use upon the common.

Newspaper references to regular organised cricket matches began appearing in the 1840s.

The main team of note was Peckham Rye Albion. Initial reports from 1847 were not promising.

Evening matches against Croydon Clarence (that’s a team, not a man) and West Wickham were curtailed due to the late arrival of the Peckham team.

The following year however, The Era newspaper reported a match on the Rye between Peckham and East Sheen. The hosts won handsomely.

The “scientific” batting of Castell, Elliott, Allsop and Sedgely was “much admired and applauded by the large concourse of respectable persons that were present.” The report concluded by demanding that “The long-stopping of Mr. Thompson must not be forgotten.”

In 1850, a match against Mitcham Albion was likely not forgotten for more malevolent reasons.

According to club secretary Allsop, the opponents swore at his team when given out, colluded in an invasion of their tent by 200 “young sweary ruffians” and threw balls at the Peckham batsmen’s heads when “they knew they were being shamefully beaten.”

The match then appears to have been abandoned. Although rarely due to opponent meltdown, being hit by a cricket ball was a regular hazard in matches on the Rye.

Lumpy pitches made it hard for batsmen to know whether the ball was aiming for their head or the wickets.

Cricketers were almost daily the subjects of injuries, many serious, eyes seemingly particularly prone to damage.

But it wasn’t just players who were under fire. Spectators, often hemmed in by several matches at once, had to be constantly wary of incoming missiles flying from all directions.

On neighbouring streets, women, children and the elderly, it was reported, could not approach the common for fear of “safety to life or limb.”

Men passing by seem to have been spared. Why was that? Did the batsmen aim? The Camberwell Vestry – the Southwark council of its day – sought action.

Could cricketers be prosecuted for injuries caused or windows smashed? Should common officials be given more powers to discourage mighty swings of the bat?

What this might entail wasn’t agreed. Perhaps they were expected to ask batsmen if they would mind not hitting the ball quite so far.

Other suggestions were more long-sighted and sympathetic to the game. Why, mooted the secretary of Glengall cricket club in 1889, could there not be a portion of ground kept apart and properly tended?

In 1890, this sentiment was echoed by The Illustrated London News.

Supporting local efforts to extend the common, the paper pinpointed the inadequacies of the current area in terms of accommodating “the large number of the artisan class bent on recreation,” especially during the cricket season.

On one particular Saturday afternoon of 1893, The Sporting Life reported “matches going on in every direction upon the far-famed Rye” – 24 of them.

The solution was not to reduce pitch numbers or ask cricketers to hit the ball less hard, but to consider the 48 acres of meadow and woodland immediately south of the common.

This was Homestall Farm, and the owners were willing to sell. When, in 1894, the area opened as Peckham Rye Park, 12 acres were reserved for cricket pitches.

There were two teams, however, who upped stumps from the treacherous common turf before the park existed, and who both later excelled.

They set up on well-maintained new grounds the other side of Colyton Road.

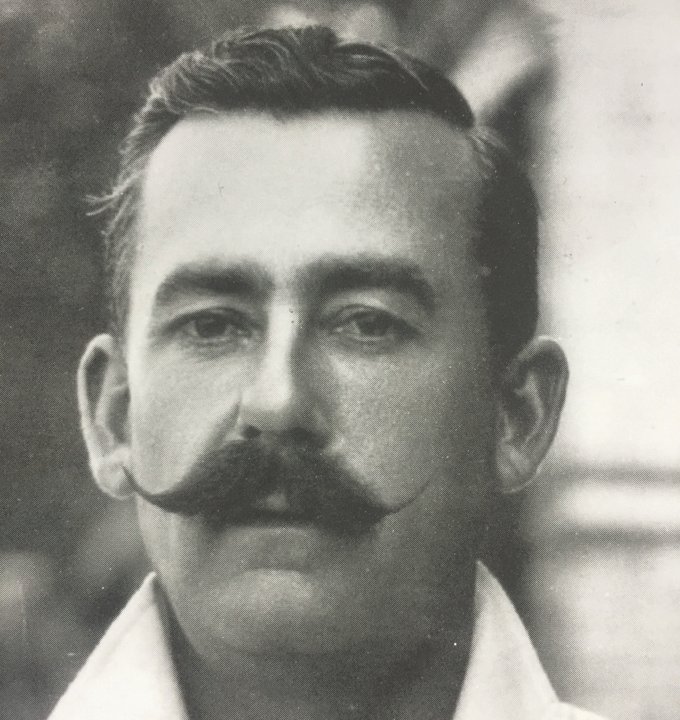

One, Honor Oak, based where Athenlay FC now play, was connected with Surrey Cricket Club, several players going on to represent the county and also England – most notably Ernie Hayes, ‘Pride of the Oak’.

The other club was Marlborough.

In the 20th century, both clubs moved to grounds on Dulwich Common, Honor Oak subsequently merging with Alleyn Old Boys and Marlborough merging with another ancient South London team to become Streatham and Marlborough.

So back in 2020, there was a pleasing connectivity watching children from the latter team christen the nets with cricketers from Surrey, the county team associated with Honor Oak Cricket Club, and all but a Ben Stokes throw away from the old Colyton Road cricket pitches.

Nets instigator Martin Koder said: “I know from playing in my school’s dads’ team against the other dads that there is definitely a big local eco-system here of cricket players.

“When I spoke to other schools, they were all very keen to get the kids involved, so the demand was there. There’s plenty of football pitches – nothing against football – but I thought let’s get people playing cricket as well.”

And thus it has come to pass – cricket is back at the Rye.