Friends of Brinkley had a short life expectancy

Gaining the benefits from a will fraudulently obtained and eliminating the witness was last week’s backdrop to the sensational poisonings, that the press labelled The Chelsea Mystery and The Croydon Poison Mystery. Today, thanks to Jan Bondeson, we find out if suspect Richard Brinkley is guilty or not…

At the coroner’s inquest on Laura Jane Glenn, William Ridgeley’s son, the 17-year-old Richard William Ridgeley, gave evidence on his father’s behalf.

Importantly, he admitted that although Ridgeley was his proper name, he sometimes used the name Brinkley!

His father’s intentions towards the deceased had been fully honourable, and he had in fact employed her to keep house for him.

When the elder ‘Ridgeley’ faced a hostile questioning about what use he made of this great quantity of dangerous poisons, he told them about his great sympathy for ailing canines, and also about some chemical and electrical experiments he was making.

He had been very fond of the deceased, and he had bought her a ring and a sewing machine. ‘Ridgeley’ described himself as a friend and helper of London’s downtrodden young ‘unfortunates’, but the coroner did not believe a word of what he was saying.

Mrs Childs, the landlady at No 21 Marlborough Square, described her experiences with the sinister ‘Mr Ridgeley’ and the silly young Laura Jane Glenn, who was fond of telling ‘porkies’ about her father being an army captain, her mother a Maid of Honour to the Queen, and the opera singer Adelina Patti one of her best friends!

In reality, she had been kicked out by her family after stealing £10, and she had been living in sin with an army soldier before moving in with ‘Ridgeley’.

After deliberating for half an hour, the coroner’s jury returned a verdict of suicide, adding that ‘Ridgeley’ deserved severe censure for having such a quantity of poison in his possession.

The police ought to find out “how he came possessed of them, and for what purpose”.

But although the police detectives still suspected that ‘Ridgeley’ had murdered Laura Jane Glenn, they were unable to find any further conclusive evidence against him.

Interestingly, they found another ‘unfortunate’ young woman, who called herself Emily George.

She had once cohabited with the talented Richard Brinkley, who sometimes used the name William Rigby.

She had three illegitimate children with him, one of whom had died mysteriously at an early age.

The ‘dog doctor’ Brinkley had often dosed her and the children with various powders and tinctures from his medicine chest, and she had sometimes felt very ill after taking her medicine.

In 1890, Brinkley had been sentenced to nine months of hard labour for stealing a quantity of bicycles and skates from a store.

Detective Inspector George Jeffrey, who led the retrospective police investigation into Brinkley’s past misdeeds, could report that the volatile Emily George had once attracted notice in Salisbury, where she had moved, by declaring that if she liked to open her mouth, she could get Brinkley sent to penal servitude for life.

Inspector Jeffrey also retrieved the death certificate of ‘George Brinkley’, aged just three hours, dead from ‘congenital debilitude’ in late 1889.

Then there was the matter of another young London floozie, the 20-year-old Jane Kemp, who had lived with Brinkley for a while in 1888 and 1889.

She gave birth to a male child named Charles Richard Kemp, who died in July 1889. The mother followed him into the grave four months later, from what was believed to be ‘consumption’.

Dead people do not talk, but the various close friends of the talented Mr Brinkley certainly had a very short life expectancy!

In The Secret History of Great Crimes, a small book published in the 1920s, the Brighton journalist and cinematograph owner Walter Harold Speer quoted a Scotland Yard detective involved in the Laura Jane Glenn case as saying that the ‘Chelsea Mystery’ had been a very black case, and that ‘Ridgeley’ had been fortunate not to have been charged with murder.

Speer added that there was no doubt in his own mind that ‘Ridgeley’ “had poisoned the girl, and, in fact, public opinion became so hot against the man that he thought it advisable to leave the neighbourhood.”

Speer went to Brinkley’s former lodgings in Brixton, where the landlady gave him an arsenic pill, which this miscreant had left behind after experimenting on her chickens. He also learnt that Brinkley’s young wife had died unexpectedly after a very unhappy life.

W. Harold Speer decided to keep an eye on this slippery customer, and he could report that after his narrow escape in the Laura Jane Glenn case, Brinkley had made himself scarce.

He was active as a street agitator, preaching socialism to crowds of labouring men in the Hammersmith street corners.

In 1900, he took his employer to court for wrongfully detaining his tools, after he had been dismissed from his job as a foreman carpenter, and won his case.

When he was on trial for the murder of Richard and Elizabeth Beck at the Surrey Assizes in Guildford, things were not looking good for the mysterious Mr Brinkley.

Reliable witnesses made it clear that he had brought the bottle of poisoned stout to 32 Churchill Road.

The problem was that he had clearly not intended the Becks to be his victims, but the judge informed the jury that if the prisoner had taken poison into the house with the intent to murder some person, it did not matter who, then he was guilty.

Found guilty of murder and sentenced to death, Richard Brinkley was hanged at Wandsworth Prison on August 13, 1907.

The most remarkable aspect of the Brinkley case is how such an unremarkable man, a hard-working teetotaller and Freemason, could concoct such a deliberate murder plot.

And how many people had this mystery man done to death? His wife, his mistress Laura Jane Glenn, several other floozies he has associated with, and more than one of his illegitimate children, had all died under suspicious circumstances.

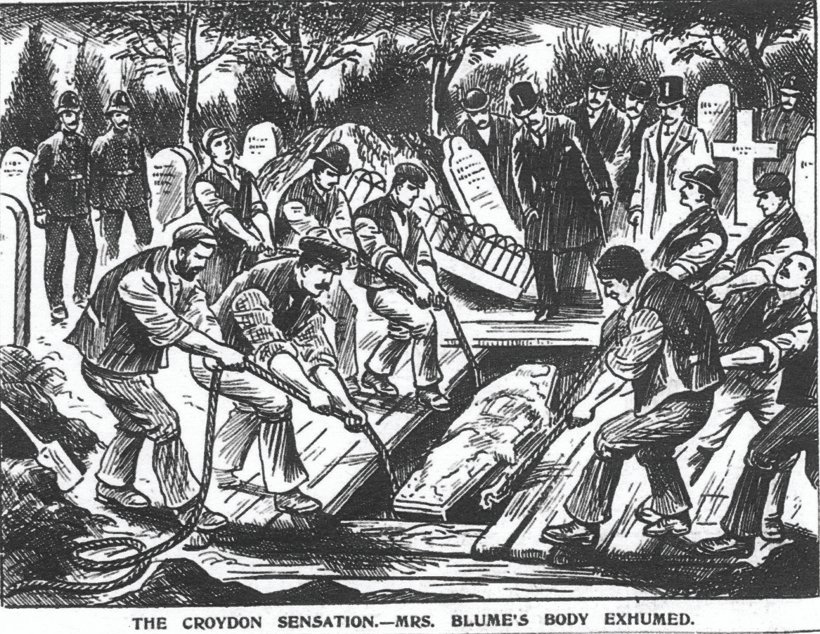

It would seem very likely that old Mrs Blume had also received a dose of poison, after Brinkley had forged her will, although this could never be proven at the time.

It was unwise of Brinkley to try to murder Parker instead of swearing him into the plot, and clumsy of him to leave the bottle behind with the Becks.

But the greatest question still remains to be answered – what had the talented Mr Brinkley, who had such an interest in London’s prostitutes, been up to in 1888, the year of Jack the Ripper?

This is an edited extract from Jan Bondeson’s Murder Houses of South London (Troubador Publishing, Leicester 2021).

Main Pic: Reginald Parker holding the large and sturdy bulldog that was intended to guard Brinkley’s ill-gotten gains, from the Illustrated Police Budget, June 1 1907