December 1994: London’s underworld pay tribute to Buster Edwards, the great train robber

On December 9, 1994, London’s underworld gathered en masse to pay their final respects to one of their heroes – a key player in the Great Train Robbery.

Crowds of thousands flocked to say their last goodbyes to Buster Edwards, one of the men who managed to pull off one of the most audacious robberies of the 20th century.

Outside the terraced houses of Rainbow Street, Camberwell, villains mingled with family and friends of the small-time crook who hit the big time 30 years earlier.

Two wreaths in the shape of trains accompanied his funeral cortege and hundreds of floral tributes lined the streets while mourners shielded his widow from the hungry media.

Edwards was born in Lambeth, the son of a barman. After leaving school, he worked in a sausage factory, where he allegedly began his criminal career by stealing meat to sell on the post-war black market.

Standing at 5ft. 6in. tall, Edwards was small but stocky with a fresh complexion and dark brown hair. A keen boxer, he became well known as “Buster” in South London boxing quarters.

After completing his national service in the RAF, Edwards brought The Walk In Club, a drinking club in Lambeth Walk where he began his life as a professional criminal.

On August 8, 1963, a Travelling Post Office train left Glasgow for Euston.

The second carriage from the front of the train was a High Value Package carriage, where registered mail was sorted.

The train passed Leighton Buzzard at about 3am. Moments later the driver, Jack Mills saw a red signal ahead at a place called Sears Crossing.

The signal was false. When Mr Mills stopped, his co-driver David Whitby climbed out of the diesel engine to ring the signalman.

The cables from the line-side phone had been cut, as he turned to return to the train he was attacked and thrown down the steep railway embankment.

According to writer Piers Paul Read, author of the 1978 book The Train Robbers, Edwards insisted in interviews that he was responsible for the hit on Jack Mills.

Meanwhile, robbers broke into the train’s carriages and, forming a human chain, removed 120 sacks containing two-and-a-half-tons of money.

The gang consisted of 15 criminals, predominantly from South London.

Battersea-born Charlie Wilson was the group’s treasurer. He gave the robbers their cut of the haul: £150,000 each.

Most of the gang were soon captured, tried, and imprisoned but Edwards evaded arrest, along with his £150,000 share of the stolen money, much of which was never recovered.

Edwards and his family left their home in Faunce Street, Kennington Park, soon after the robbery.

They joined another leading gang member, Bruce Reynolds, and fled to Mexico.

Eventually, the money ran out, and Edwards’ negotiated his return to England, in 1966.

He surrendered and was sentenced to 15 years in jail. He was the 14th person to be convicted for their part in the robbery.

In 1964, 13 men received prison sentences of up to 30 years for their various roles.

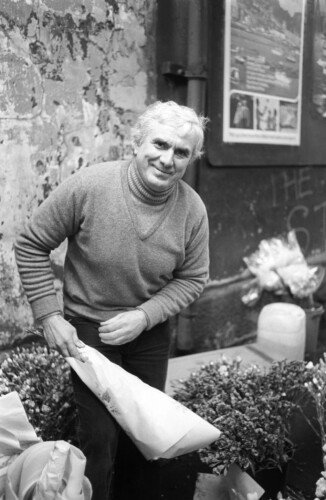

Upon his early release from prison, in 1975, Edwards tried to stay on the right side of the law and ran a flower stall in Lower Marsh, Waterloo.

In a magazine interview, he said: “I know I’m lucky to have got a chance to have this stall and be my own boss but it’s so dreary compared with the life I used to lead.

“It wasn’t even the money. I’ve been on jobs that haven’t netted me a penny but, oh, does the adrenaline flow.”

Later in life Buster developed depression, worsened by a tendency to turn to alcohol.

He was found by his brother hanging from a steel girder in a lock-up garage in Leake Street on November 28, 1994. He was 63 years old.

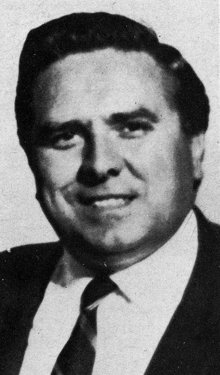

Pictured top: From left, Buster Edwards, Tommy Wiseby, Jim White, Bruce Reynolds, Roger Cordrey, Charles Wilson and Jim Hussey, the seven men involved in the Great train Robbery of 1963 (Picture: PA Images / Alamy Stock Photo)