The New Cross Fire – How ’13 dead and nothing said’ energised a generation

Forty years ago on January 18, Yvonne Ruddock and Angela Jackson held a joint birthday party at a house in New Cross. The celebration was to end in tragedy after a fire ripped through the house in the early hours of the morning. A total of 13 young black people died. Rumours spread that the attack had been racially motivated. The tragedy politicised the black community as the minimal response from the police, public, and government sparked the slogan “13 dead, nothing said”. Two inquests were held to find out the cause. Both recorded open verdicts. On the anniversary of the blaze that rocked Britain, TOBY PORTER looks at its legacy.

It was a party to celebrate the birthdays of Yvonne Ruddock and Angela Jackson at 439 New Cross Road.

But it ended in tragedy during the early hours of January 18, 1981 when 13 people died as a result of a fire.

Those who died in the fire were: Humphrey Brown, 18; Peter Campbell, 18; Steve Collins, 17; Patrick Cummings, 16; Gerry Francis, 17; Andrew Gooding, 14; Lloyd Richard Hall, 20; Patricia Denise Johnston, 15; Rosalind Henry, 16; Glenton Powell, 15; Paul Ruddock, 22; Yvonne Ruddock, 16; Owen Thompson, 16.

Another partygoer, Anthony Berbeck, died 18 months later, never having come to terms with his friends’ deaths.

They were all black.

In the aftermath of the inferno, rumours spread that it was the result of a deliberate attack, possibly caused by a racist throwing a petrol bomb through a window.

At the time of the fire, police investigating it argued that they did not have enough evidence or witnesses.

Despite the police investigation being reopened after 16 years and two inquests, the precise cause of the fire has never been established and nobody has ever been charged in relation to the blaze.

The chairman of the support group set up to find out what happened that fateful night at 439 New Cross Road dismissed the petrol bomb rumours.

New Cross Fire Parents Committee chairman George Francis lost his 17-year-old son Gerry in the blaze. He said: “Some said it was a firebomb and it was a racist attack.

“We as parents tended to believe that. But as the days went by and police did forensic tests, it changed. If you throw something at a window you’d expect glass to be found inside the house. “But it wasn’t. So that tells you that whatever happened, happened inside the house. So I can’t believe it was a racist attack at all.”

Even 10 years ago, Mr Francis feared he might never live to discover what happened. He said: “We wonder what our son would have been like. Every year reminds us.

“Gerry had talked about becoming a veterinary surgeon and loved his music.

“On the day of the party he asked me if I would drive a van to the house full of his music stuff, such as speakers, but I didn’t.

“We lived in Devonshire Road in Forest Hill at the time and he left the house that day, gave his mother a kiss, and said, ‘Dad, I will see you in the morning’.

“But that morning never came.”

MOTHER OF TWO LOST HUSBAND AND NIECE

Sandra Ruddock was pregnant with her second child when police knocked on the door to say her husband Paul had been seriously burnt in the fire.

Paul died three weeks after the blaze tore through his sister Yvonne’s 16th birthday party. His sister was among the other 12 who died.

Sandra had been at the scene of the blaze until 4.30pm that day. She said: “I was at the house earlier on but was pregnant at the time and had another five-year-old child who was tired and wanted to go to sleep.

“The next thing I knew I had two police officers at my door at 8.30 in the morning to tell me my husband had been injured.

“I was in and out of the hospital visiting him for the next few weeks, trying to keep calm because I was pregnant and didn’t want to risk having a miscarriage.

“I was in a trance during this whole period, it was the only way I could cope.

“We are still nowhere near knowing how the kids died.

“That second inquest was just a waste of time.

“I have my own theory on what happened but I won’t say what.

“When police were first looking at things it was made into a racial thing by people.

“It had nothing to do with that. It was just something that happened.”

Wayne Hayes, who was 17 at the time, recalled how teenagers were jumping out of second-floor windows, how it was so hot “people’s skin was peeling back” and how in the aftermath he had 140 skin grafts. He shattered 163 bones and has been classed as disabled ever since.

“It started in the basement with a naked flame,” told HuffPost. “It was something that happened and it just went too far.”

BLACK PEOPLE’S DAY OF ACTION

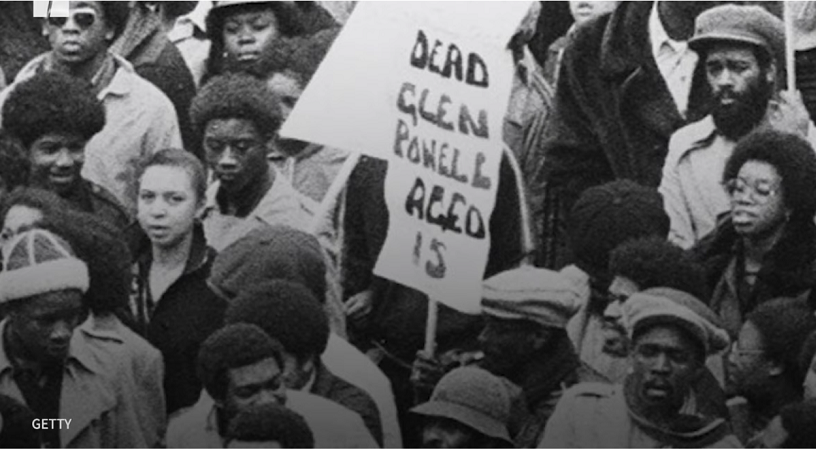

A meeting was held on 20 January, attended by 300 people, including anti-racist groups. They established the New Cross Massacre Committee (NCMC) and a fact-finding commission, which interviewed witnesses and ensured survivors had legal support. Hundreds of people met on January 25 1981 at the Moonshot Club and marched in protest.

A month after the blaze, there was another fire in Dublin, which killed nearly 50 people at a club. The prime minister Margaret Thatcher expressed condolences quickly, but that didn’t happen for New Cross.

Velvetina Francis, whose 17-year-old son, Gerry, died in the fire, said in a BBC interview aired in 1981: “Had it been white kids, she would have been on the television, on the radio, and sent her sympathy.”

Six weeks after the fire, on March 2, an estimated 20,000 people marched for eight hours through London in what was known as the Black People’s Day of Action.

They assembled in Fordham Park, New Cross and marched through the streets of London, over the course of eight hours, to Hyde Park to commemorate the lives of the victims and protest against the treatment of the case, both by the police and the media.

As the marchers passed through the streets of South London, workers walked out of their offices to join in, and children and young people scaled the fences of their schools to take part.

Young women and men defied police as they crossed the river at Blackfriars to take the protest directly to the home of the British print media in Fleet Street.

Many of the organisers and demonstrators were leading voices in the black community – Linton Kwesi Johnson, Alex Pascall, Darcus Howe, John La Rose, Stuart Hall, Sybil Phoenix and Menelik Shabazz.

The protest, organised by the NCMC, was then the largest demonstration by the black community in the UK.

Pioneering dub poet Johnson described the march as a watershed moment. He said: “It made the British establishment sit up and take note of the fact that we weren’t powerless. We were able to mobilise that power in defence of our human rights.”

THE INQUESTS AND MEMORIALS

The first inquest was held just months after the blaze in 1981 but recorded an open verdict. A second inquest in 2004, left families frustrated after retired judge Gerald Butler, appointed as deputy coroner, again recorded the same result – in other words, there was no decision on whether it was on purpose or an accident.

Coroner Gerald Butler said in his verdict: “While I think it probable that this fire was begun by deliberate application of a flame to the armchair near to the television, I cannot be sure of this. The result is this, that in the case of each and every one of the deaths, I must return an open verdict.”

In 1971, a Caribbean house party had been attacked by firebomb in Sunderland Road, in nearby Forest Hill, leaving 22 injured. And just three years before in 1978, Deptford’s Albany Empire community theatre was burned down, with the National Front claiming responsibility.

In 2002, Lewisham council installed a stained-glass window in their memory at St Andrew’s Church in Brockley Road, Brockley, where many of the young people who died had been members of a youth club.

A plaque was also unveiled at 439 New Cross Road, on the 30th anniversary.

The following year, a stone memorial was installed in Fordham Park, Deptford, listing those who died; facing the stone memorial is a bench with a memorial inscription.